Shostakovich was the soloist at the premiere of this 1st Piano Concerto, also known as Concerto For Piano And Trumpet because of the prominent part for the trumpet. At the premiere, Shostakovich had the trumpet player sit next to the piano instead of with the rest of the orchestra, which is usually done in modern performances as well. The concerto was premiered in 1933, before Shostakovich's first official government censure. The concerto is in 4 movements:

I. Allegretto - The piano and orchestra toss out the themes in this movement while the trumpet comments on them. The mood of the movement changes quickly. This is some of Shostakovich's most sarcastic, witty and pithy music and it is reminiscent of the spontaneity of the first symphony. The movement ends with a dialogue with piano and trumpet.

II. Lento - This movement opens with a slow waltz-like melody. The piano enters, and expands the waltz into a passionate outburst from the piano and orchestra. After the climax fades, the strings re-enter gently, with the trumpet playing the waltz theme (with none of the sarcasm of the first movement) over the accompaniment of the orchestra. The piano and orchestra combine for a heart-felt, gentle close to the movement.

III. Moderato - This movement is less than 2 minutes long, and is generally thought to act as an introduction to the final movement. It is played with weight and depth of tone by the strings, but the piano shines through the quasi-seriousness and the music segues into the finale...

IV. Allegro con brio - The tempo increases, the piano chatters away. In this movement the trumpet becomes more prominent, almost on a par with the piano. The music becomes manic in tempo and intensity. Shostakovich was fond of quoting motifs from his and other composers music. This movement makes reference to Haydn, Mahler, a Jewish folk song, and others. The cadenza for solo piano is derived from Beethoven's Rage Over A Lost Penny for piano solo. The music gets more and more animated, until the trumpet plays a repeated figure while the piano and orchestra pound out chords. The entire ensemble joins together to bring the music to a rousing finish.

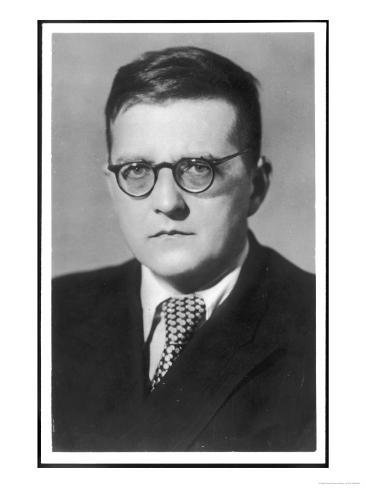

Shostakovich was in his late 20's when he wrote this concerto. His music was everywhere, his fame and popularity assured. In this period of relative freedom to do what he pleased, he composed a concerto that wavers from giddy to serious, music that toys with the listener. After the fiasco instigated by his opera of 1936 Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, Shostakovich's life would change, along with his music, to a certain degree. But all that was to come. For the moment, Shostakovich wrote a concerto that thumbed its nose at tradition.