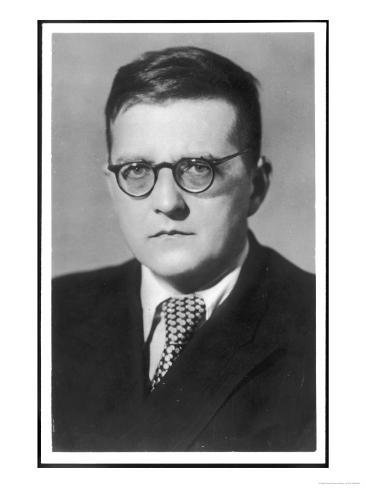

When politics is mixed with art, the artist needs to beware. Shostakovich is a case in point. During the Second World War, the Soviet Union used the music of Shostakovich as a rallying cry for the defeat of Nazi aggression. Shostakovich wrote parts of his 7th Symphony, nicknamed 'Leningrad' during the 900-day Nazi siege of Leningrad. That symphony in particular was not only used by the Soviet Union as a propaganda tool, but the symphony was internationally popular during the war as a representation of opposition to Nazi totalitarianism and militarism. How ironic that the citizen of a totalitarian nation created art that was used against another totalitarian nation! But so it goes in the world of international politics where finger pointing many times is used as a diversionary tactic so no one will notice what you are doing.

Shostakovich was treated as a national hero, at least on the surface. He still remembered the official condemnations (Stalin's decree filtered through the voice of a music critic in the official part newspaper Pravda) he suffered through in the 1930's. Shostakovich's next symphony, Number Eight, written in 1943, was a long, brooding work that kept up the theme (at least on the surface) of Soviet suffering during the war. Shostakovich had learned to write music on different levels of meaning since his official censure, so this symphony, like the seventh, had more to do with Shostakovich's feelings about the Russian people's suffering (and his own) than any official theme. But he stayed in the good graces of the powers that be (translate that to Stalin) with the Eighth Symphony.

Fast forward to 1945 and the end of the war. Shostakovich already was thinking about his Ninth Symphony in 1944, a work the composer said himself would be a celebratory work over the defeat of Nazi Germany, complete with soloists and chorus. After the past two huge symphonies, the expectation was a work of huge dimensions in keeping with the ninth symphonies of Beethoven, Dvorak, Bruckner and Mahler. The composer said he already had part of the massive first movement written in early 1945. He set aside the composition for three months and completed it later in 1945.

Whatever happened during that three moth hiatus is not known, but the Ninth Symphony turned out to be nothing like the composer had promised. It is a short work, more like a Haydn symphony in form and mood, far from the triumphant victory symphony that was expected. Shostakovich himself said of the work, "Musicians will like to play it, and critics will delight in blasting it." The initial reception was favorable, but less than a year after the premiere, the work was officially banned and the composer denounced. The composer was in the official dog house once again.

The symphony is in five movements, the last three played without pause:

I Allegro - A Haydenesque movement in classical sonata form. The trombone and piccolo have prominent roles as the orchestra plays in a jovial mood.

II.Moderato - Music that is in a controlled, restrained, melancholy mood.

III. Presto - A nose-thumbing scherzo that prances along until...

IV. Largo - The brass introduces the bassoon as soloist in sad, mournful music, and then...

V. Allegretto - Allegro - The bassoon changes its 'tune' into a tongue in cheek melody that snickers in the low register of the instrument, which leads into a edgy, folk dance-like music that zips along until the orchestra scurries to an end.

Shostakovich's musical personality can be very complex. From bombast to beautiful, from official kow-towing to nose-thumbing independence. He spent the majority of his life in conflict between his artistic nature and what was officially demanded of him. He managed to resolve this conflict somewhat by basically composing two kinds of works; works that came from his artistic heart and works to try and satisfy the powers that be. Sometimes the music is obvious which kind it is, sometimes Shostakovich manages to blur the two, as with his Fifth Symphony. But with the Ninth Symphony there is no blur. It is a short, witty and joyous work that occasionally grows serious. In other words, it is full of changing moods and emotions, but seldom gets too serious. He knew it was not the work expected of him. He knew he would mostly likely get in trouble once again. He probably didn't breathe any easier after the premiere and the initial favorable response. He knew the 'system' well enough to be wary. And he was right. But he wrote the symphony as his talent dictated, had it performed and took the consequences. It may not have been as much an act of artistic courage but of artistic necessity. Whatever the reason or the cause, the Ninth Symphony is one of Shostakovich's most accessible and well-written compositions.

No comments:

Post a Comment