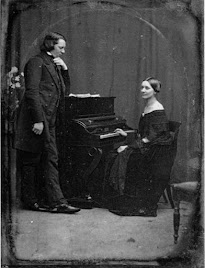

In 1853 when Johannes Brahms was 19, he made a concert tour as accompanist to the violinist Eduard Reményi. On the tour he met Franz Liszt (where tradition has it that he fell asleep while Liszt played the piano) and Joseph Joachim, violinist and composer. Joachim became a good friend and gave Brahms a letter of introduction to Robert Schumann. Later in 1853 Brahms traveled to Düsseldorf and proceeded to impress and enchant both Robert Schumann and his wife Clara.

Brahms stayed with the Schumann's for a few days, and Robert was so impressed with the music he heard from the young composer that he wrote an article for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal of Music) announcing Brahms to the musical world. The article titled Neue Bahnen (New Paths) begins with Schumann writing briefly about new and upcoming composers until he reveals the name of Brahms:

Robert and Clara Schumann ...I thought of the paths of these chosen ones that pursued the art of music with the greatest participation, there must suddenly appear one who would be appointed to utter the highest expression of time ideally, one who did not bring us the championship gradually, but, like Minerva, would spring from the head of Zeus fully formed. And he has come, a young blood, at whose cradle Graces and Heroes stood guard. His name is Johannes Brahms... His appearance announced to us: this is an anointed one. Sitting at the piano he revealed wonderful regions. We were drawn into ever widening circles, which made an orchestra of wailing and loud cheering voices from the piano. There were sonatas, more like veiled symphonies; songs whose poetry you without knowing the words would understand, although a deep singing melody passed through all; single piano pieces, partly demonic, partly of the most graceful form; then sonatas for Violin and piano; Quartets for strings; and each so different from the others... May the highest Genius strengthen his genius!

High praise that did as much harm as good, for it put undue pressure on a 20-year old composer that

was still finding his way. Brahms was self-critical by nature, and this passing of the mantle made him even more so.

When Schumann attempted suicide in early 1854, he voluntarily had himself put into a mental hospital for Clara and his children's sake. Brahms lived in the Schumann household intermittently from that time until Schumann's death in 1856. During this time he wrote two piano quartets, No. 1 In G minor opus 25, and No. 2 In A Major opus 26. He also drafted a third piano quartet in C-sharp minor, but this one wasn't to achieve its final form until almost twenty years later.

|

| Young Werther |

After revising and rewriting, the third piano quartet was finally completed in 1874. The home key of the work was dropped to C minor from C-sharp minor with the quartet becoming one of Brahms most dramatic chamber works. The nickname 'Werther' came from Brahms acquaintance with Goethe's novel The Sorrows of Young Werther that deals with a young man that falls in love with a woman that is already married, and so Werther commits suicide. The parallels in Brahms' life in 1855 when the work was begun are evident, for he fell in love with Clara Schumann at the time. There is no clue whether this love remained platonic or became intimate, but Brahms well remembered the feelings he had in 1855 when he told his publisher his idea for a cover page for the printed score of the piano quartet:

On the cover you must have a picture, namely a head with a pistol to it. Now you can form some conception of the music! I’ll send you my photograph for the purpose.

Brahms remained somewhat dissatisfied with the work as it didn't have its premiere until 1875, a year after it was published. It is in 4 movements:

I. Allegro non troppo - Brahms was labeled as a musical conservative by the followers of the 'New Music' of Liszt and Wagner for a number of reasons, not least of all for his keeping with tradition by writing in the traditional forms of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. The writing of chamber music especially was considered old fashioned. But Brahms was did not slavishly keep to an academic model of these forms. He utilized sonata form in the broadest sense of the term, and was innovative in ways to use it. It is never an easy task to technically make your way through a major work of Brahms. The relationships of themes are often blurred as themes appear different that are actually closely related. And his use of modulation between keys is far from conservative. The first movement of this quartet is a good example of how he used all of these elements within a traditional form to suit his musical expression. This movement was one of the original two movement he wrote in 1855 for the quartet. It begins with octaves by the piano which are answered by a sighing figure. The piano again plays bare octaves, and is answered with a slight variant of the sighing theme. A short development leads to a downward figure that brings in the first theme. The second theme is first heard in the solo piano, after which there are 4 variations, each eight measures long like the theme. A variant of the first theme brings the exposition to a close. After a short section based on previous material, what appears to be a new theme in B major is loudly stated:

This theme is stated again in a different key and leads to the working out of the second theme which goes through a short series of variations once again. The sighing motives from the beginning of the work return signalling the recapitulation, this time the opening theme is heard in the key of E minor. The second theme is now heard in the key of G major and goes through a small number of variations for the third time. The first theme is then developed until it ends in C major. A short coda repeats the figures with slight variations that opened the movement, and the music ends quietly.

II. Scherzo: Allegro - This movement was perhaps composed in the 1860's, between the initial composition of the work and the final version. It is in C minor, the same key as the first movement. The music is terse and coarse as the scherzo plays through until a quasi-trio section begins with a new theme but continues in the same mood. The scherzo returns and is slightly shortened. A short coda brings the movement to a close with a Picardy Third, a term for the closing of a work in a minor mode with a major chord:

III. Andante - This movement along with the first movement is part of the music of the draft written in 1855. It is in E major, a key of four sharps that is somewhat far removed from the home key of C minor with 3 flats. It is the only movement of the quartet not in C minor. It begins with a long, sweet melody for the cello (an instrument that Brahms studied briefly in his youth) with piano accompaniment:The piano's role in this movement is one of gentle support as the strings sing a song of tender calm, a possible love song for Clara Schumann.

IV. Finale: Allegro comodo - The final movement returns to C minor and the piano plays a restless theme under the theme played by the violin:

The second theme is derived from the piano accompaniment of the opening theme of the movement and is played by violin and viola. The exposition is repeated. After the development works through themes and relationships of fragments, the recapitulation replays the violin theme of the beginning in all three stringed instruments with broken octaves in the piano. Themes are expanded until a coda is heralded by the piano playing thick chords in an outline of the second theme. The piano resumes its initial figure in a hushed tone along with the strings until two loud C major chords end the work.