Monday, July 15, 2024

Liszt - Six Consolations

Thursday, May 2, 2024

Brahms - Piano Quartet No. 3 In C Minor, Opus 60 'Werther'

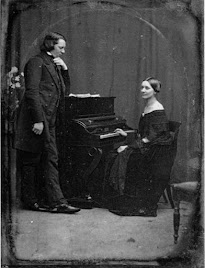

Robert and Clara Schumann ...I thought of the paths of these chosen ones that pursued the art of music with the greatest participation, there must suddenly appear one who would be appointed to utter the highest expression of time ideally, one who did not bring us the championship gradually, but, like Minerva, would spring from the head of Zeus fully formed. And he has come, a young blood, at whose cradle Graces and Heroes stood guard. His name is Johannes Brahms... His appearance announced to us: this is an anointed one. Sitting at the piano he revealed wonderful regions. We were drawn into ever widening circles, which made an orchestra of wailing and loud cheering voices from the piano. There were sonatas, more like veiled symphonies; songs whose poetry you without knowing the words would understand, although a deep singing melody passed through all; single piano pieces, partly demonic, partly of the most graceful form; then sonatas for Violin and piano; Quartets for strings; and each so different from the others... May the highest Genius strengthen his genius!

|

| Young Werther |

On the cover you must have a picture, namely a head with a pistol to it. Now you can form some conception of the music! I’ll send you my photograph for the purpose.

The piano's role in this movement is one of gentle support as the strings sing a song of tender calm, a possible love song for Clara Schumann.

IV. Finale: Allegro comodo - The final movement returns to C minor and the piano plays a restless theme under the theme played by the violin:

The second theme is derived from the piano accompaniment of the opening theme of the movement and is played by violin and viola. The exposition is repeated. After the development works through themes and relationships of fragments, the recapitulation replays the violin theme of the beginning in all three stringed instruments with broken octaves in the piano. Themes are expanded until a coda is heralded by the piano playing thick chords in an outline of the second theme. The piano resumes its initial figure in a hushed tone along with the strings until two loud C major chords end the work.

Saturday, April 20, 2024

Schubert - String Quartet No. 14 In D Minor 'Death and The Maiden'

Pass me by! Oh, pass me by!

Go, fierce man of bones!

I am still young! Go, rather,

And do not touch me.

And do not touch me.

Death:

Give me your hand, you beautiful and tender form!

I am a friend, and come not to punish.

Be of good cheer! I am not fierce,

Softly shall you sleep in my arms!

Saturday, February 24, 2024

Schubert - Piano Sonata No. 21 In B-flat Major, D. 960

Despite his illness, Schubert continued to compose one work after the other. Starting in the spring of 1828 he composed many works, among them a Mass, various piano pieces, many songs that were printed posthumously in a collection titled Schwanengesang, as well as the three final piano sonatas. In September of 1828 his health took a turn for the worse and his doctor advised him move out of the city, so he moved into his brother Ferdinand's house which was in the suburbs of Vienna. Up until the very last weeks of his life Schubert continued to compose until he no longer was able. Schubert finished his last piano sonata on September 26, 1828. He died November 19, 1828. He was but 31 years old.

The last three piano sonatas were not published until ten years after Schubert's death. Schubert's piano sonatas were neglected during most of the 19th century. His other music came to be revered, but the common opinion about his piano sonatas were that they were inferior to his other works. Even Robert Schumann, to whom the publisher of the last sonatas dedicated the works, was of this opinion:

Whether they were written from his sickbed or not, I have been unable to determine. The music would suggest that they were. And yet it is possible that one imagines things when the portentous designation, ‘last works,’ crowds one’s fantasy with thoughts of impending death. Be that as may, these sonatas strike me as differing conspicuously from his others, particularly in a much greater simplicity of invention, in a voluntary renunciation of brilliant novelty—an area in which he otherwise made heavy demands upon himself—and in the spinning out of certain general musical ideas instead of adding new threads to them from phrase to phrase, as was otherwise his custom. It is as though there could be no ending, nor any embarrassment about what should come next. Even musically and melodically it ripples along from page to page, interrupted here and there by single more abrupt impulses—which quickly subside.An exception to this 19th century opinion was Brahms, who was fond of the sonatas and studied them intensely. The sonatas continued to be neglected until early in the 20th century when a handful of pianists like Artur Schnabel championed the works and played them in recitals. The last piano sonata is in 4 movements:

I. Molto moderato - No doubt one of the reasons for the negative attitudes about this piano sonata is the inordinate length of the first movement. This first movement averages about twenty minutes if the exposition repeat is taken, which is as long as many complete sonatas. Because of the length of this movement some pianists do not take the exposition repeat, thus shortening the work. The exposition repeat became somewhat of an option with later composers, but with Schubert it is essential. There are many things that differentiate the later sonatas from the earlier ones, one of which is the long, lyrical themes that take time to unfold, which contribute to the length of movements. The first theme of this movement begins with a theme that is calm and lyrical. This theme is interrupted by a trill on G-flat, a most unusual interruption that sounds foreign harmonically, almost sinister. The theme resumes after this intrusion and is then slightly developed by means of a key change to G-flat. Schubert modulates back to the tonal center of B-flat for the rest of the theme. Schubert then introduces what amounts to a long transition to the second main theme of the movement. He begins this transition material in the key of F-sharp minor, moves the home key and then the second theme makes its appearance in the key of F major. More transition material appears before the music of the first ending of the exposition appears, music that is unique and not heard again in the movement. The exposition is repeated verbatim, except for new transition material that leads to the development section. The development section is extensive and modulates quite often to many different keys. The development section comes to an end with the repeat of the mysterious trill on G-flat. The recapitulation repeats the exposition material with the obligatory changes in key to the home key of B-flat major. A short coda brings back the first theme along with the trill on G-flat and the movement ends in B-flat major.

II. Andante sustenuto - Schubert has more harmonic surprises in the second movement. It begins in C-sharp minor, a key that played a role in the development section of the previous movement. The theme is a sad one that is intensified by the accompaniment that covers the bottom, middle and top of the keyboard. A contrasting middle section begins in A major and does its share of harmonic roaming. The first theme returns with some slight alterations. The mood is still sad, but the alterations in the accompaniment have given it an added tension. The theme modulates and finally comes to rest in C-sharp major and the movement ends quietly.

III. Scherzo: Allegro vivace con delicatezza - The scherzo is in B-flat major and lightens up the mood of two preceding brooding movements. The trio section is in B-flat minor and Schubert creates rhythmic instability by tying notes over the bar line and accenting notes in the left hand, sometimes on the beat, sometimes off the beat. The scherzo is repeated and with a very short coda it comes to a close.

IV. Allegro ma non troppo – Presto - A movement in sonata form with three main themes. The first is in B-flat major and begins with an octave on G. This is repeated each time the first subject is played. The second theme is more mobile and in F major. The third theme begins with a sharp double forte outburst in F minor. After the third theme is played through, material from the first theme leads directly to the development as the exposition is not repeated. The development section deals with the first theme only. The three themes are repeated in the recapitulation, and the work ends with a coda that is marked presto.

Monday, January 29, 2024

Berlioz - Grande Messe Des Morts (Requiem) Opus 5

|

| Dome of Les Invalides |

The Requiem is in ten sections:

1) Requiem et Kyrie

Grant them eternal rest, O Lord,

2) Dies Irae -

Day of wrath, that day

François Habeneck "Because of my habitual suspicion, I had posted myself behind [conductor François] Habeneck. With my back to his, I was watching the group of timpani players, which he could not see, as the moment approached when they were to take part in the general mêlée. There are perhaps a thousand bars in my Requiem. At precisely the point I have been speaking of, when the tempo broadens and the brass instruments launch their awesome fanfare, in the one bar where the role of the conductor is absolutely indispensable, Habeneck lowered his baton, quietly pulled out his snuff box and started to take a pinch of snuff. I was still looking in his direction. Immediately I pivoted on my heels, rushed in front of him, stretched out my arms and indicated the four main beats of the new tempo. The orchestras followed me, everything went off as planned, I continued to conduct to the end of the piece, and the effect I had dreamed of was achieved. When at the last words of the chorus Habeneck saw that the Tuba mirum was saved: "What a cold sweat I had, "he said, "without you we were lost!" Yes, I know very well," I replied, looking straight at him. I did not add a word … Did he do it on purpose?… "

What then shall I say, wretch that I am,

4) Rex Tremendae

King of awful majesty.

5) Quaerens Me

Seeking me You did sit down weary

Mournful that day

Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory,

deliver the souls of all the

faithful departed from the pains

of hell and from the bottomless pit.

And let St. Michael Your standard

bearer lead them into the holy

light which once You did promise

to Abraham and his seed,

Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

this sacrifice of prayer and praise.

Receive it for those souls

whom today we commemorate.

Holy, holy, holy, God of Hosts.

Heaven and earth are full

of Your glory. Hosanna in the highest.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins

of the world, grant them eternal rest.

You, O God, are praised in Zion

and unto You shall the vow be

performed in Jerusalem. Hear my

prayer, unto You shall all flesh come.

Grant the dead eternal rest,

O Lord, and may perpetual light shine

on them, with Your saints for ever,

Lord, because You are merciful.

Amen.

Friday, January 12, 2024

Mozart - Rondo For Piano In A Minor K. 511

Friday, December 8, 2023

Rachmaninoff - Symphonic Dances, Opus 45

It was the time of the modernists like Schoenberg and Stravinsky, who each in their own style changed the world of classical music for composers and audiences. Rachmaninoff's music looked backwards instead of forwards. Indeed, his previous composition, the Third Symphony, was akin to the Symphonic Dances as it reflected his past. Rachmaninoff himself knew this better than anyone else. Interviewed in 1939, he admitted:

I feel like a ghost wandering in a world grown alien. I cannot cast out the old way of writing and I cannot acquire the new. I have made an intense effort to feel the musical manner of today, but it will not come to me.

After leaving Russia at a time of great political and cultural upheaval in 1917, Rachmaninoff eventually made his way to the United States and relied on his incredible piano technique and conducting skills to make a living for himself and family. He grew to become financially well-off, so much so that he could afford another home in Lucerne, Switzerland, where he would spend time during the concert off season. It was there that he composed most of his later works. Symphonic Dances was the only major work that was composed in The United States.

I. Non allegro - The music begins quietly with the ticking of strings and the commentary of solo woodwinds in turn. The music turns loud with drums punctuating a rhythmic drive that continues throughout the first section. A piano joins in as the rhythmic dance continues. instruments in turn enter and make their comments, almost like the music is a concerto for orchestra. The first section winds down as the oboe and clarinet herald the beginning of the middle section which is carried by a solo saxophone. The saxophone makes few appearances in the symphony orchestra, but Rachmaninoff's use of it makes a listener wonder why. The tone of the instrument blends nicely with the rest of the woodwinds. Rachmaninoff may have written in a less than modern style for the time, but there is no doubting his skill and talent for orchestration and melody.

The first section returns with brilliance as Rachmaninoff continues to showcase the differing timbres of the orchestral instruments. As the movement begins to wind down, a new theme is played by the strings and accompanied by piano, glockenspiel, and harp. This theme is a reworking of a theme from his 1st Symphony, which was heard only once in 1897 in Russia. The work had a disastrous premiere, and Rachmaninoff abandoned it. After the reminiscence of the theme, the movement quietly ends with short snippets of the beginning.

II. Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) - It is indeed a waltz as Rachmaninoff designates, but it begins in 6/8 time rather than the usual 3/4 time of a waltz. Rachmaninoff visits the waltz form with ingenuity, a continuation of instrument spotlighting and nostalgia, with some eerie sounds thrown in, like the sounds of muted horns and trumpets. There is a solo for violin that leads the proceedings. There is an atmosphere of haunted dreaminess in the music. The pace quickens near the end, as the instruments (or dancers) scurry off the dance floor.

III. Lento assai - Allegro vivace - After the poor reception of his Third Symphony in 1936, Rachmaninoff vowed to cease composing. His career of concert pianist and conductor were taking up most of his time, and felt underappreciated as a composer. But it wasn't the first time that he had tried to give up composing. After the disaster of his First Symphony, he stopped composing for three years. And like so many years ago, the inner drive for creative work returned to him in 1940 when he wrote the Symphonic Dances. The final movement has the same basic A-B-A form as the other two, and it shares the brilliance in orchestration as well. A section from his setting of the Russian Orthodox All Night Vigil is used, along with what was a somewhat ubiquitous theme for Rachmaninoff, the Latin hymn Dies irae. The Dies irae theme was referenced in many of his compositions.

The movement begins with a reworking of snippets of the Dies irae, punctuated by bells and other percussion. The Dies irae continues with syncopations until a climax is reached. A different, more laid-back version of the theme is heard in low strings with the glissandos of harps. parts of the Russian Orthodox litany is also heard. The middle section is in contrast to the two turbulent outer sections, with parts of it vaguely similar to the Dies irae theme that are more tranquil. The final section brings back the Dies irae theme, but this time it is in competition with a Russian chant Blessed Is The Lord. The Russian chant wins out, and a new theme, Allilyua, taken from his 1915 work for chorus All-Night Vigil. The work ends in a blaze of rhythmic percussion and full orchestra.

Rachmaninoff was 67 years old when he wrote Symphonic Dances, and his many years of extensive traveling, piano playing (piano players are prone to bad backs and arthritis), and cigarette smoking took a toll on his health. The concert season of 1939 was especially tiring for him, and he himself said after writing the work, "It must have been my final spark". He was a deeply religious man, and at the end of the manuscript he wrote, "I thank thee, Lord."