The Czech folk music that Antonín Dvořák heard all his life had its own tradition of pentatonic scale usage. He used it many times himself in his compositions long before he came to New York city in 1892. He took a great interest in Native American music as well as Negro spirituals, and understood them quite well. For a homesick Bohemian they may have struck a familiar chord (or melody) within his ears.

He composed the Symphony No. 9 in 1893, and while American music inspired him, he did not use any American melodies in the work. He wrote in the American style of pentatonic scale use and did it so well that for a long time many put the cart before the horse, especially in regards to the melody from the 2nd movement. A song named Goin' Home takes its melody from the symphony, not the other way around. The words were not set to the melody until many years after the symphony had been written.

He composed the Symphony No. 9 in 1893, and while American music inspired him, he did not use any American melodies in the work. He wrote in the American style of pentatonic scale use and did it so well that for a long time many put the cart before the horse, especially in regards to the melody from the 2nd movement. A song named Goin' Home takes its melody from the symphony, not the other way around. The words were not set to the melody until many years after the symphony had been written.The premiere of the work was the greatest success of Dvořák's career, as each movement was applauded so much that he had to take a bow after each. He had created interest in the work months before its premiere when he was quoted in New York newspapers as saying that an American school of composition should be built around Negro and Native American melodies. In a late 19th century American culture that was openly prejudiced against both groups, Dvořák's words created controversy as well as a great deal of curiosity about the work. Carnegie Hall was packed the night of the premiere, as Dvořák's son Otakar relates:

There was such demand for tickets for the gala premiere of the New World Symphony that, in order to fully satisfy the potential audience, Carnegie Hall, huge as it is, still had to increase the number of seats severalfold. All the newspapers competed with one another in their commentaries, reflecting on whether father’s symphony would determine the further development of American music and, in doing so, they succeeded in enveloping the work in an aura of exclusivity, even before the premiere had taken place. Its success was so immense that it was beyond ordinary imagining, and it is surely to the credit of the American public that they are able to appreciate the music of a living composer. Even after the first movement the audience unexpectedly burst into lengthy applause. After the breathtaking Largo of the second movement, they would not let the concert proceed until father had appeared on the podium to receive an ovation from the delighted audience in the middle of the work. Once the symphony had ended, the people were simply ecstatic. Father probably had to step up onto the podium with conductor Anton Seidl twenty times to take his bow before a euphoric audience. He was very happy.The work was taken up by orchestras the world over, and it became one of the most performed works in the repertoire. As with other often-played works in the repertoire, The New World Symphony has been called a warhorse, as over-familiarity can breed contempt with some ears. But it is a work that repays listening to with new ears, for it is a masterpiece that can yield new pleasures for the attentive, unjaded ear. The symphony is in four movements:

I. Adagio - Allegro molto - The slow introduction begins the movement with a motive in irregular rhythms that anticipate what is to come. Woodwinds repeat this motive. After a short rest the music increases to fortissimo with strings, horns and timpani. The music recedes and then builds up to a climax. Strings hold a tremolo, reduce the volume to pianissimo and the horns enter with the first theme. After the theme plays out, a section of dotted rhythm leads up to the second theme played in the woodwinds, and then the violins. A third theme appears, this is the theme that resembles the spiritual Swing Low Sweet Chariot, and then the exposition is repeated. The development section deals with the main theme primarily, and puts the theme through many key changes and drama. The recapitulation plays through the themes until the coda is reached. The music gains in speed and drama as the orchestra runs to the end and collapses in loud chords.

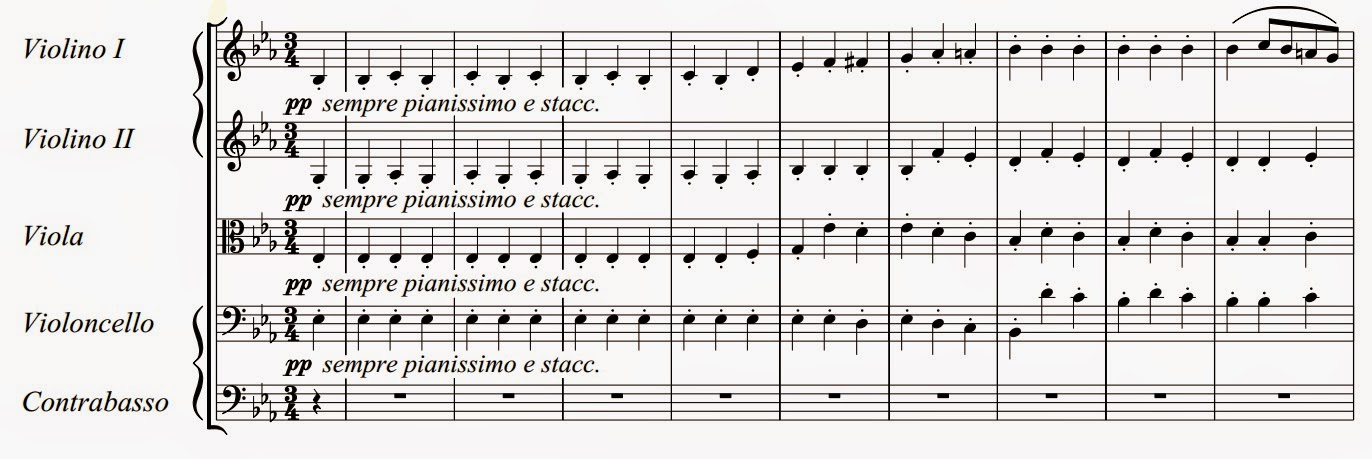

II. Largo - A remarkable progression of chords in the woodwinds and brass acts as an introduction to the slow movement. The famous melody for cor anglais plays over a subdued accompaniment. A section for strings leads to a repeat of the melody. A middle section plays a plaintive melody over agitated strings, and continues in sounds of lonesome wandering. The music brightens, the tempo quickens as a section is played that recalls the cor anglais melody as well as the main theme from the first movement. The melody appears once again in the cor anglais, and then is taken up by two of each string instrument. The phrases of the melody are interrupted by halting rests and the music slowly makes its way to a return of the chord progression of the introduction. The music fades and ends with two barely audible chords in the low strings.

III. Scherzo: Molto vivace - Poco sostenuto - Dvořák likened this music to the feast ofwild dancing as depicted in Longfellow's poem Song of Hiawatha. Music of off-accents, powerful rhythms and sounds grows more docile in the next part of the theme. A triangle gives color to the relative calm of this section. The boisterous dancing returns until the music fades into the next thematic section which is also accented by the triangle and by trills in the woodwinds and strings. The wild dance returns until a coda brings back the first theme of the first movement as well as a reference to the third theme of the first movement before it all comes to a powerful end.

IV. Allegro con fuoco - Written in sonata form, Dvořák combines new material with material heard in the other movements. The first subject is a powerful one heard in the brass. The clarinet sings the second theme. The third theme is given by the strings with accents by the trumpets. The development section begins with a recall of the first theme of the first movement. The cor anglais melody of the second movement is then heard. In one notable section he combines the main themes of the second, third and fourth movement. The final movement is a summing up of all that has gone before, and Dvořák builds to a tremendous climax in a coda that includes the introductory chords to the second movement. The primary themes of the last movement combine with the primary theme of the first movement, and the music dies away in E major.

While for the most part the work was received quite well, William Apthorp, a Boston newspaper music critic reflects the level of prejudices held byh some of the time against new music, foreign composers and so-called barbaric Negro music:

The great bane of the present Slavic and Scandinavian Schools is and has been the attempt to make civilized music by civilized methods out of essentially barbaric material… …Our American Negro music has every element of barbarism to be found in the Slavic or Scandinavian folk-songs; it is essentially barbarous music.