Franz Schubert composed over 600 Lieder in his short life from 1797-1828. Schubert not only was one of the great melodists of all time; he created a symbiosis with the solo voice and the piano, the instrument most associated with German Lieder. The piano reflects, imitates, enhances and sometimes contrasts the voice instead of merely accompanying it. Schubert's creativity and imagination influenced most of the German song composers that came after him, as well as composers in other countries.

In 1828, Schubert was afflicted with what turned out to be a fatal illness. The illness that took his life isn't known for certain with theories ranging from tertiary stage syphilis to typhoid fever. He continued to compose and between fever, nausea, crippling headaches and joint pain wrote some of his most well-known works in the last months of his life. One of these final works was a set of Lieder that was published a few months after Schubert's death in a collection titled Schwanengesang by the Viennese publisher Tobias Haslinger. The title was taken from the Greek legend that states that swans sing a beautiful song just before they die. The collection has been called a song cycle, but Schubert used 14 poems by 3 different poets whereas most song cycles are written to poems by one poet that have a common theme between them.

Many thanks to Celia Sgroi for allowing free use of her excellent translations of all 14 of the German poems. The first 7 songs are to poems by Ludwig Rellstab, German poet and critic. The poems were originally offered in 1825 to Beethoven, but were passed on to Schubert after Beethoven's death in 1827:

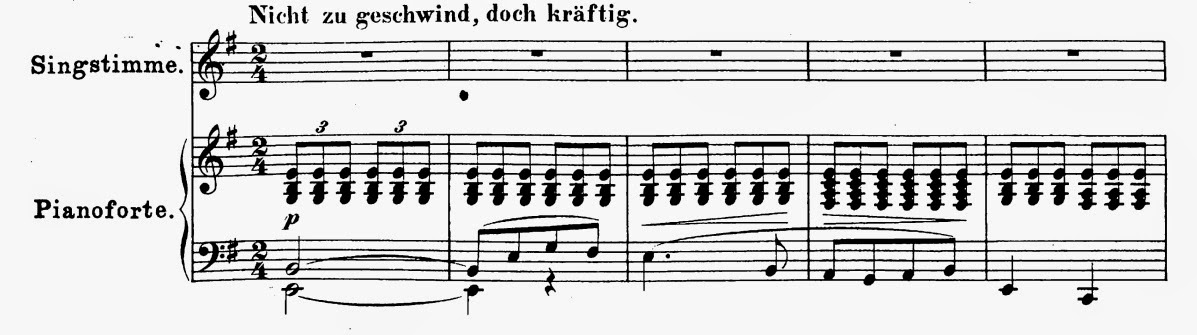

1. Liebesbotschaft (Message Of Love) - The singer invites a stream to carry a note to his lover. Schubert begins the song with the solo piano in music that imitates a rippling stream, an ear-visual that Schubert used many times in his songs:

The piano continues the stream illusion throughout.

Rushing brook,

So pretty and clear,

Will you hurry to my sweetheart

So cheerful and quick?

Ah, dear little brook,

Be my messenger;

Bring greetings

To her from afar.

All of her flowers,

Tended in the garden,

That she wears so sweetly

On her breast,

And her roses,

In crimson radiance,

Brook, refresh them

With your cooling stream.

When on the stream bank,

lost in dreams

thinking of me,

she bows her head,

comfort my dearest

with your friendly glance,

for her beloved is

coming back soon.

When the sun is setting

With its red glow,

lull my beloved off to sleep.

Murmuring, rock her

To her sweet rest,

And whisper dreams

Of love to her.

2. Kriegers Ahnung (Soldier's Foreboding) - A soldier sings about how much he misses his beloved while he is afield with his fellow soldiers:

Around me in deep silence

Lie my soldier comrades;

My heart is so anxious and heavy,

So aflame with longing.

How often have I dreamed sweetly

On her warm breast!

How friendly was the stove’s warmth

When she lay in my arms!

Here, where the brooding glow of flames,

Alas, only shines on weapons,

Here my heart feels totally alone,

And tears of sadness flow.

Heart! Don’t let solace abandon you!

Many a battle is ahead.

Soon I’ll rest and sleep soundly,

My beloved—good night!

3. Frühlingssehnsucht (Longing In Spring) - Springtime with all its beauty surrounds the singer but loneliness and longing for his beloved cause sadness among the flowers:

Murmuring breezes flutter so gently

Fill me sighing with the scent of flowers!

How you greet me with a blissful sigh!

What have you done to my pounding heart?

It wants to follow your airy trail!

Where to?

Brooks, so cheerfully bubbling as well,

Flow sparkling silver down to the glen.

The billowing wave hastens downhill!

The meadows and sky are reflected deep within.

Why do you draw me, urgent, yearning feeling,

Down there?

Sparkling gold of the greeting sun,

You bring me hopeful bliss so sweet!

How your joyfully greeting image refreshes me.

It smiles so gently in the dark blue sky

And has filled my eye with tears!

Why?

The forests and hills are wreathed in green,

A snowfall of blossoms sparkles and gleams.

Everything surges to the nuptial light;

The seeds are burgeoning, the buds are opening,

They’ve found what they need to blossom:

And you?

Restless longing, yearning heart,

Nothing but tears, complaints, and pain?

I too am aware of a growing urge!

Who’ll finally quiet my urgent desire?

Only you can release the spring in my soul,

Only you!

4. Ständchen (Serenade) - The singer urges a lover for a tryst at the grove of trees in the valley. One of Schubert's most recognizable melodies, this song shifts between minor and major keys to convey the singer's longing:

Softly my songs implore

You through the night;

Down into the quiet grove,

Beloved, come to me!

Slender treetops rustle, murmur

In the moon’s radiance;

Don’t fear the hidden listener’s

malice, my dearest.

Do you hear the nightingales singing?

Ah, they appeal to you,

With their sweet plaintive tones

They’re pleading for me.

They understand the heart’s yearning,

They know the pain of love,

Touch with their silvery tones

Every feeling heart.

Let them move you, too,

My darling, listen to me!

Trembling, I await you!

Come, dearest, enrapture me.

5. Aufenthalt (Resting Place) - A song that conveys emotional pain and anguish that is as powerful and never ending as waves of the sea, wind in the treetops and the core of a mountain. The piano sets the tension in the beginning of the song as it plays constant triplet chords in the right hand against a melody in the left hand that contains eighth notes that create a compound rhythm of 2 versus 3:

Thundering torrent,

Roaring forest,

Stony crag,

My resting place.

Just as the waves roll

One after one,

My tears are flowing

Eternally new.

As high in the treetops

It billows and seethes,

Just as unceasingly

Beats my heart.

And like the mountain’s

Ancient core,

Ever the same

Remains my pain.

6. In der Ferne (In The Distance) - A broken-hearted lover flees their friends, mother's house, and home town to wander the world to escape the one that broke their heart. Heavy, mournful chords accompany the sorrow of the singer.

Woe to the fugitive,

Fleeing the world!

Roaming foreign places,

Forgetting his homeland,

Hating his mother’s house,

Leaving his friends

Alas, no blessing follows

Along their ways.

Heart that is yearning,

Eye that is weeping

Longing that never ends,

Turning toward home.

Breast that is stirring,

Lament that is fading,

Evening star twinkling,

Hopelessly sinking!

Breezes, you rippling,

Waves gently ruffling,

Sunbeam hastening

Nowhere remaining:

She who with agony

Broke my loyal heart—

Greetings from the fugitive,

Fleeing the world!

7. Abschied (Farewell) - This song is also about leaving, but this one is in contrast to the previous one. The departing singer bids a fond farewell to a town that they have enjoyed. The reason why they must depart isn't known, only that it is time to go. The singer welcomes his companions, the sun during the day and the stars at night. The piano imitates the singer's trotting horse as he leaves without looking back:

Goodbye! You jolly, you cheerful town, goodbye!

My horse paws the ground now with light-hearted hoof,

Now receive my final, my parting salute

You’ve never seen me downcast before,

And it can’t happen now at my farewell.

Goodbye, you trees, you gardens so green, goodbye!

Now I’m riding along the silvery stream,

My farewell song echoes far and wide,

You never heard a sorrowful song from me,

And you won’t hear one now at my departure.

Goodbye, you friendly lasses there, goodbye!

Why do you look out of your flower-perfumed house

With such a flirtatious and alluring glance?

As always I greet you and look around

But I never turn my horse back.

Goodbye, dear sun, now go to your rest, goodbye!

Now the gold of the twinkling stars shimmers.

How much do I love you stars in the sky;

We travel the world both far and wide,

And everywhere you are my loyal guide.

Goodbye, you shimmering bright window, goodbye!

You sparkle so homelike in the twilight glow

And invite us so trustfully into your cottage.

Alas, I’ve ridden by here so many times,

And is today to be the final time?

Goodbye, you stars, hide yourself in grayness, goodbye!

The dark, fading light of the window

Can’t be replaced by you countless stars,

I can’t linger here, I have to go on,

What matter if you follow me so faithfully!

The next 6 songs are by Heinrich Heine, one of the giants of German literature. Heine got into trouble with the authorities in Germany for his radical politics and spent the last 25 years of his life in Paris. The six poems of Heine are shorter and more intense than the previous seven.

8. Der Atlas (Atlas) - In heavy, agitated music, the singer agonizes about the crushing emotional pain he carries that is as heavy as the burden of the entire world that the Titan Atlas carries on his back.

I, wretched Atlas, a world

The whole world of pain I must carry,

I bear the unbearable, and my heart

Is breaking in my body.

You proud heart, you wanted it so!

You wanted to be happy, eternally happy,

Or eternally miserable, proud heart,

And now you are in misery.

9. Ihr Bild (Her Portrait) - Another song about lost love, this time the singer looks at a mental image of his lost beloved. The piano plays the singer's melody in the beginning that reflects the imagined image of the beloved:

After the singer imagines his beloved, the reality that he has lost her is enforced by the starkness of the piano's ending cadence.

I stood in dark dreams

And stared at her image,

And the beloved visage

Quietly came to life.

Upon her lips appeared

A smile so wonderful,

And as if from tears of sadness

Her eyes sparkled.

And my tears flowed as well

Down from my cheeks—

And oh, I just can’t believe,

That I have lost you!

10. Das Fischermädchen (The Fisher Girl) - The singer tries to coax a girl to romance and in an attempt to get her to trust him compares his heart to the ocean that has many treasures inside. The piano has a gentle rocking rhythm throughout that imitates the sea lapping at the shore.

You lovely fisher girl,

Row your boat to shore;

Come to me and sit down,

We’ll cuddle hand in hand.

Lay your head on my breast

And don’t be so afraid;

You trust yourself without care

Daily to the untamed sea.

My heart is like the ocean,

Has storm and ebb and flood,

And many a lovely pearl

Rests in its depths.

11. Die Stadt (The Town) - A man rows a boat towards a town. When he sees the spires of the town emerge in the distant fog he laments the place where he lost his lover. Schubert instructs the pianist to use the damper pedal to blur the tremolos in the left hand in imitation of the fog. When the right hand enters it plays a nine-note figure that represents the spires of the town seen through the fog:

On the distant horizon

Appears like a cloud-image

The town with its spires

Shrouded in the gloom of evening.

A damp breeze ruffles

The green surface of the water;

In a mournful rhythm rows

The boatman in my craft.

The sun rises once again

Glowing above the earth

And shows me that spot

Where I lost my beloved.

12. Am Meer (At The Seashore) - A song about a meeting in a hut at the seashore, and in typical Romantic era excess, tears were shed (and drank by the lover). But all is not well as the singer laments that the woman has poisoned him with her tears. There are two emotional sections in the song when the piano begins tremolos in both hands that reach a crescendo. Where in a previous song about the ocean the water laps the shore almost playfully, here the waves lugubriously thud against the shore, underlining the dilemma of the singer.

The sea sparkled far and wide

In the last glow of evening;

We sat at the lonely fisherman’s hut,

We sat silent and alone.

The fog rose, the water surged.

The gull flew back and forth;

From your lovely eyes

The tears dropped.

I saw them fall upon your hand

And fell on my knees;

And from your white hand

I drank away the tears.

Since that time my body pines

My soul is dying with yearning;

The wretched woman

Poisoned me with her tears.

13. Der Doppelgänger (The Ghostly Double) - The singer looks at a house where his lover used to live. He sees another man standing by the house in anguish, and then he realizes that the other man is actually his ghostly double that is going through the same sorrow he did long ago. One of Schubert's most eerie songs, the piano begins with a four bar section that is repeated, giving the impression of a passacaglia. But the bass changes with the ostinato returning but in a different key. The dynamic range for the piano goes from pianissimo to triple forte, which gives the soloist tremendous crescendos that tax the singer's capacity as the Doppelgänger is recognized. The major chord that ends the song does not ease the tension much.

The night is quiet, the streets are silent,

My beloved lived in this house;

She left the town a long time ago,

But the house still stands in the same place.

A man stands there, too, and stares upward

And wrings his hands with the force of his pain;

I’m horrified when I see his face—

The moon shows me my own likeness.

You ghostly double, you pallid fellow!

Why do you ape my lovesickness,

That tormented me here

So many nights long ago?

The final poem was written by Johann Gabriel Seidl, an Austrian scientist and poet. The poem was included by the first publisher because it was thought to be the last song Schubert wrote.

14. Die Taubenpost (The Courier Pigeon) - Schubert didn't always write music to poems of the masters. Schubert's gift for melody and song construction was so great that he could set most anything to music if he set his mind to it. This song is about someone who compares his longing to a courier pigeon.

I have a courier pigeon in my employ,

It’s very devoted and true.

It never stops short of my goal

And never flies too far.

I send it out many thousand times

With messages every day,

Away past many a pretty place,

Right to my dearest’s house.

It peeks through the window secretly there

And watches for her step and glance,

Gives her my greetings playfully

And brings hers back to me.

I don’t need to write notes anymore

I send my tears with it instead,

I’m sure they will never go astray,

It serves me so eagerly.

By night, by day, awake, in dreams,

It’s all the same to it,

If it can only rove and roam,

That is repayment enough.

It never tires, it never flags,

The way is ever new,

It needs no lure, it needs no pay,

The dove is so loyal to me!

And so I keep it close to my heart

Assured of the sweetest reward;

Its name is—longing! Do you know it?

Enduring love’s messenger.

Many thanks to Celia Sgroi for allowing free use of her excellent translations of all 14 of the German poems. The first 7 songs are to poems by Ludwig Rellstab, German poet and critic. The poems were originally offered in 1825 to Beethoven, but were passed on to Schubert after Beethoven's death in 1827:

1. Liebesbotschaft (Message Of Love) - The singer invites a stream to carry a note to his lover. Schubert begins the song with the solo piano in music that imitates a rippling stream, an ear-visual that Schubert used many times in his songs:

The piano continues the stream illusion throughout.

Rushing brook,

So pretty and clear,

Will you hurry to my sweetheart

So cheerful and quick?

Ah, dear little brook,

Be my messenger;

Bring greetings

To her from afar.

All of her flowers,

Tended in the garden,

That she wears so sweetly

On her breast,

And her roses,

In crimson radiance,

Brook, refresh them

With your cooling stream.

When on the stream bank,

lost in dreams

thinking of me,

she bows her head,

comfort my dearest

with your friendly glance,

for her beloved is

coming back soon.

When the sun is setting

With its red glow,

lull my beloved off to sleep.

Murmuring, rock her

To her sweet rest,

And whisper dreams

Of love to her.

2. Kriegers Ahnung (Soldier's Foreboding) - A soldier sings about how much he misses his beloved while he is afield with his fellow soldiers:

Around me in deep silence

Lie my soldier comrades;

My heart is so anxious and heavy,

So aflame with longing.

How often have I dreamed sweetly

On her warm breast!

How friendly was the stove’s warmth

When she lay in my arms!

Here, where the brooding glow of flames,

Alas, only shines on weapons,

Here my heart feels totally alone,

And tears of sadness flow.

Heart! Don’t let solace abandon you!

Many a battle is ahead.

Soon I’ll rest and sleep soundly,

My beloved—good night!

3. Frühlingssehnsucht (Longing In Spring) - Springtime with all its beauty surrounds the singer but loneliness and longing for his beloved cause sadness among the flowers:

Murmuring breezes flutter so gently

Fill me sighing with the scent of flowers!

How you greet me with a blissful sigh!

What have you done to my pounding heart?

It wants to follow your airy trail!

Where to?

Brooks, so cheerfully bubbling as well,

Flow sparkling silver down to the glen.

The billowing wave hastens downhill!

The meadows and sky are reflected deep within.

Why do you draw me, urgent, yearning feeling,

Down there?

Sparkling gold of the greeting sun,

You bring me hopeful bliss so sweet!

How your joyfully greeting image refreshes me.

It smiles so gently in the dark blue sky

And has filled my eye with tears!

Why?

The forests and hills are wreathed in green,

A snowfall of blossoms sparkles and gleams.

Everything surges to the nuptial light;

The seeds are burgeoning, the buds are opening,

They’ve found what they need to blossom:

And you?

Restless longing, yearning heart,

Nothing but tears, complaints, and pain?

I too am aware of a growing urge!

Who’ll finally quiet my urgent desire?

Only you can release the spring in my soul,

Only you!

4. Ständchen (Serenade) - The singer urges a lover for a tryst at the grove of trees in the valley. One of Schubert's most recognizable melodies, this song shifts between minor and major keys to convey the singer's longing:

|

| Ludwig Rellstab |

You through the night;

Down into the quiet grove,

Beloved, come to me!

Slender treetops rustle, murmur

In the moon’s radiance;

Don’t fear the hidden listener’s

malice, my dearest.

Do you hear the nightingales singing?

Ah, they appeal to you,

With their sweet plaintive tones

They’re pleading for me.

They understand the heart’s yearning,

They know the pain of love,

Touch with their silvery tones

Every feeling heart.

Let them move you, too,

My darling, listen to me!

Trembling, I await you!

Come, dearest, enrapture me.

5. Aufenthalt (Resting Place) - A song that conveys emotional pain and anguish that is as powerful and never ending as waves of the sea, wind in the treetops and the core of a mountain. The piano sets the tension in the beginning of the song as it plays constant triplet chords in the right hand against a melody in the left hand that contains eighth notes that create a compound rhythm of 2 versus 3:

Thundering torrent,

Roaring forest,

Stony crag,

My resting place.

Just as the waves roll

One after one,

My tears are flowing

Eternally new.

As high in the treetops

It billows and seethes,

Just as unceasingly

Beats my heart.

And like the mountain’s

Ancient core,

Ever the same

Remains my pain.

6. In der Ferne (In The Distance) - A broken-hearted lover flees their friends, mother's house, and home town to wander the world to escape the one that broke their heart. Heavy, mournful chords accompany the sorrow of the singer.

Woe to the fugitive,

Fleeing the world!

Roaming foreign places,

Forgetting his homeland,

Hating his mother’s house,

Leaving his friends

Alas, no blessing follows

Along their ways.

Heart that is yearning,

Eye that is weeping

Longing that never ends,

Turning toward home.

Breast that is stirring,

Lament that is fading,

Evening star twinkling,

Hopelessly sinking!

Breezes, you rippling,

Waves gently ruffling,

Sunbeam hastening

Nowhere remaining:

She who with agony

Broke my loyal heart—

Greetings from the fugitive,

Fleeing the world!

7. Abschied (Farewell) - This song is also about leaving, but this one is in contrast to the previous one. The departing singer bids a fond farewell to a town that they have enjoyed. The reason why they must depart isn't known, only that it is time to go. The singer welcomes his companions, the sun during the day and the stars at night. The piano imitates the singer's trotting horse as he leaves without looking back:

Goodbye! You jolly, you cheerful town, goodbye!

My horse paws the ground now with light-hearted hoof,

Now receive my final, my parting salute

You’ve never seen me downcast before,

And it can’t happen now at my farewell.

Goodbye, you trees, you gardens so green, goodbye!

Now I’m riding along the silvery stream,

My farewell song echoes far and wide,

You never heard a sorrowful song from me,

And you won’t hear one now at my departure.

Goodbye, you friendly lasses there, goodbye!

Why do you look out of your flower-perfumed house

With such a flirtatious and alluring glance?

As always I greet you and look around

But I never turn my horse back.

Goodbye, dear sun, now go to your rest, goodbye!

Now the gold of the twinkling stars shimmers.

How much do I love you stars in the sky;

We travel the world both far and wide,

And everywhere you are my loyal guide.

Goodbye, you shimmering bright window, goodbye!

You sparkle so homelike in the twilight glow

And invite us so trustfully into your cottage.

Alas, I’ve ridden by here so many times,

And is today to be the final time?

Goodbye, you stars, hide yourself in grayness, goodbye!

The dark, fading light of the window

Can’t be replaced by you countless stars,

I can’t linger here, I have to go on,

What matter if you follow me so faithfully!

The next 6 songs are by Heinrich Heine, one of the giants of German literature. Heine got into trouble with the authorities in Germany for his radical politics and spent the last 25 years of his life in Paris. The six poems of Heine are shorter and more intense than the previous seven.

8. Der Atlas (Atlas) - In heavy, agitated music, the singer agonizes about the crushing emotional pain he carries that is as heavy as the burden of the entire world that the Titan Atlas carries on his back.

I, wretched Atlas, a world

The whole world of pain I must carry,

I bear the unbearable, and my heart

Is breaking in my body.

You proud heart, you wanted it so!

You wanted to be happy, eternally happy,

Or eternally miserable, proud heart,

And now you are in misery.

9. Ihr Bild (Her Portrait) - Another song about lost love, this time the singer looks at a mental image of his lost beloved. The piano plays the singer's melody in the beginning that reflects the imagined image of the beloved:

After the singer imagines his beloved, the reality that he has lost her is enforced by the starkness of the piano's ending cadence.

I stood in dark dreams

And stared at her image,

And the beloved visage

Quietly came to life.

Upon her lips appeared

A smile so wonderful,

And as if from tears of sadness

Her eyes sparkled.

And my tears flowed as well

Down from my cheeks—

And oh, I just can’t believe,

That I have lost you!

|

| Heinrich Heine |

You lovely fisher girl,

Row your boat to shore;

Come to me and sit down,

We’ll cuddle hand in hand.

Lay your head on my breast

And don’t be so afraid;

You trust yourself without care

Daily to the untamed sea.

My heart is like the ocean,

Has storm and ebb and flood,

And many a lovely pearl

Rests in its depths.

11. Die Stadt (The Town) - A man rows a boat towards a town. When he sees the spires of the town emerge in the distant fog he laments the place where he lost his lover. Schubert instructs the pianist to use the damper pedal to blur the tremolos in the left hand in imitation of the fog. When the right hand enters it plays a nine-note figure that represents the spires of the town seen through the fog:

Appears like a cloud-image

The town with its spires

Shrouded in the gloom of evening.

A damp breeze ruffles

The green surface of the water;

In a mournful rhythm rows

The boatman in my craft.

The sun rises once again

Glowing above the earth

And shows me that spot

Where I lost my beloved.

12. Am Meer (At The Seashore) - A song about a meeting in a hut at the seashore, and in typical Romantic era excess, tears were shed (and drank by the lover). But all is not well as the singer laments that the woman has poisoned him with her tears. There are two emotional sections in the song when the piano begins tremolos in both hands that reach a crescendo. Where in a previous song about the ocean the water laps the shore almost playfully, here the waves lugubriously thud against the shore, underlining the dilemma of the singer.

The sea sparkled far and wide

In the last glow of evening;

We sat at the lonely fisherman’s hut,

We sat silent and alone.

The fog rose, the water surged.

The gull flew back and forth;

From your lovely eyes

The tears dropped.

I saw them fall upon your hand

And fell on my knees;

And from your white hand

I drank away the tears.

Since that time my body pines

My soul is dying with yearning;

The wretched woman

Poisoned me with her tears.

13. Der Doppelgänger (The Ghostly Double) - The singer looks at a house where his lover used to live. He sees another man standing by the house in anguish, and then he realizes that the other man is actually his ghostly double that is going through the same sorrow he did long ago. One of Schubert's most eerie songs, the piano begins with a four bar section that is repeated, giving the impression of a passacaglia. But the bass changes with the ostinato returning but in a different key. The dynamic range for the piano goes from pianissimo to triple forte, which gives the soloist tremendous crescendos that tax the singer's capacity as the Doppelgänger is recognized. The major chord that ends the song does not ease the tension much.

The night is quiet, the streets are silent,

My beloved lived in this house;

She left the town a long time ago,

But the house still stands in the same place.

A man stands there, too, and stares upward

And wrings his hands with the force of his pain;

I’m horrified when I see his face—

The moon shows me my own likeness.

You ghostly double, you pallid fellow!

Why do you ape my lovesickness,

That tormented me here

So many nights long ago?

The final poem was written by Johann Gabriel Seidl, an Austrian scientist and poet. The poem was included by the first publisher because it was thought to be the last song Schubert wrote.

14. Die Taubenpost (The Courier Pigeon) - Schubert didn't always write music to poems of the masters. Schubert's gift for melody and song construction was so great that he could set most anything to music if he set his mind to it. This song is about someone who compares his longing to a courier pigeon.

I have a courier pigeon in my employ,

It’s very devoted and true.

|

| Johann Gabriel Seidl |

And never flies too far.

I send it out many thousand times

With messages every day,

Away past many a pretty place,

Right to my dearest’s house.

It peeks through the window secretly there

And watches for her step and glance,

Gives her my greetings playfully

And brings hers back to me.

I don’t need to write notes anymore

I send my tears with it instead,

I’m sure they will never go astray,

It serves me so eagerly.

By night, by day, awake, in dreams,

It’s all the same to it,

If it can only rove and roam,

That is repayment enough.

It never tires, it never flags,

The way is ever new,

It needs no lure, it needs no pay,

The dove is so loyal to me!

And so I keep it close to my heart

Assured of the sweetest reward;

Its name is—longing! Do you know it?

Enduring love’s messenger.