There has been much written about the 3rd Symphony of Ludwig van Beethoven, and rightly so. The work is a turning point in Beethoven's career as a composer and for western music in general. The music is daring, innovative and there is a large number of stories and anectdotes relating to the symphony's non-musical life. Without a doubt the main story of the work is the title 'Eroica' and the relationship of the music to the French leader Napoleon Bonaparte.

The standard story is that Beethoven, a man who was politically progressive, admired Napoleon, the man who ruled France after the

Revolution and

The Terror. Napoleon was himself was progressive in the sense that he sought to reform the French legal system through what came to be known as the

Napoleonic Code. The Code became very influential for all of Europe due to the influence Napoleon had on countries he had conquered as well as other countries that were allied with him. Basically the Code did away with privilege of birth, granted freedom of religion and said that government jobs should go to those most qualified. It attempted to revamp a legal system in France that was a hodge-podge of feudal traditions and laws that varied from area to area.

Beethoven wanted to dedicate a work to Napoleon early on, and there is evidence that was what he intended to do, but circumstances made him change his mind. Beethoven's pupil

Ferdinand Ries related the incident concerning the dedication:

In 1803 Beethoven composed his third symphony (now known as the Sinfonia Eroica) in Heiligenstadt, a village about one and a half hours from Vienna....In writing this symphony Beethoven had been thinking of Buonaparte, but Buonaparte while he was First Consul. At that time Beethoven had the highest esteem for him and compared him to the greatest consuls of ancient Rome. Not only I, but many of Beethoven's closer friends, saw this symphony on his table, beautifully copied in manuscript, with the word "Buonaparte" inscribed at the very top of the title-page and "Luigi van Beethoven" at the very bottom. Whether or how the intervening gap was to be filled out I do not know. I was the first to tell him the news that Buonaparte had declared himself Emperor, whereupon he broke into a rage and exclaimed, "So he is no more than a common mortal! Now, he too will tread under foot all the rights of man, indulge only his ambition; now he will think himself superior to all men, become a tyrant!" Beethoven went to the table, seized the top of the title-page, tore it in half and threw it on the floor. The page was later re-copied and it was only now that the symphony received the title 'Sinfonia Eroica.'

|

| Title page of the Third Symphony with Napoleon's name scratched out |

This is the only contemporary reporting of the incident by an eyewitness, and Beethoven's reaction may have been much more vocal and violent than Ries portrays. Beethoven's temper was legendary, and the relative calmness in Ries' retelling doesn't fit the anger and disappointment Beethoven probably felt after his hero falling off the pedestal.

But modern scholarship has found that Beethoven may have changed his mind about the dedication for a more mundane reason; if he dedicated the work to one of his patrons (along with a specific amount of time that the dedicatee had exclusive ownership of the work) he would be monetarily rewarded. There was no possibility of that if he dedicated it to Napoleon.

There is also a link between the symphony and the

Heiligenstadt Testament, a will Beethoven wrote in 1802 while he was resting in the town of Heiligenstadt. By this time Beethoven was suffering the effects of deafness, and a doctor suggested he needed to go to the small town and rest. His hearing problems were getting worse, and the thought of losing his hearing drove him to despair, all of which can be read in the will he wrote in Heiligenstadt. He came to terms with his growing deafness and dedicated himself even more fervently to his art. This resulted in stylistic changes in his music that began in 1803. The Third Symphony was the turning point in his style, and while there is proof that Beethoven had Napoleon in mind while he was writing the symphony (at least the first and second movements), it may well be that the actual hero of the title is Beethoven himself.

The Third Symphony is in four movements:

I. Allegro con brio - There is no doubt that the symphony begins in E-flat major as two loud E-flat major chords are played by the full orchestra to begin the movement. The first theme also reeks of E-flat major as the notes within the theme that is played in the cellos and basses spell out the notes of the E-flat major chord until a C-sharp is thrown into the mix. This theme is expanded and passed to different instruments of the orchestra. A second, gentler theme is played by the woodwinds. While these two themes are the primary ones in the movement, they are more like sign posts for the listener to help keep track of what's going on, for there are other short themes in the movement. A transition section segues seamlessly to the repeat of the exposition. The development begins with gentle references to themes already heard, but the music soon becomes highly dramatic as a snippet of the first theme grows in volume and complexity. The second theme makes an appearance and leads into a short fugal section that flows into loud, highly accented chords by the orchestra. Beethoven stretches and builds on themes to an extent that defies description. The music gets quiet, as the transition to the recapitulation nears. As the violins quietly saw away, the infamous early entry of the horn that plays a fragment of the first theme appears, something that baffled most listeners in Beethoven's time. Even his student Ferdinand Ries accused the horn player of playing the theme too early in the first rehearsal of the work:

Beethoven has a wicked trick for the horn; a few bars before the theme comes in again complete, Beethoven lets the horn indicate the theme where the two violins still play the chord of the second. For someone who is not familiar with the score this always gives the impression that the horn player has counted wrong and come in at the wrong place. During the first rehearsal of this symphony, which went appallingly, the horn player, however, came in correctly. I was standing next to Beethoven and, thinking it was wrong, I said, 'That damned horn player! Can't he count properly? It sounds infamously wrong!' I think I nearly had my ears boxed - Beethoven did not forgive me for a long time.

The orchestra comes together for the recapitulation and Beethoven begins to vary the first theme. Themes are repeated and modulated until the music reaches the coda, but a coda unlike any written before. This coda continues to vary and develop themes and lasts nearly as long as the exposition. The movement ends as it began with loud chords for full orchestra. This movement usually takes between 17 and 18 minutes to play if the exposition repeat is taken. Beethoven requested that the exposition be repeated (which was not always automatically done) for the sake of balance.

II. Marcia funebre: Adagio assai - If the first movement can be viewed as a tribute to a hero, the second movement is the death of the hero. After the Funeral March of

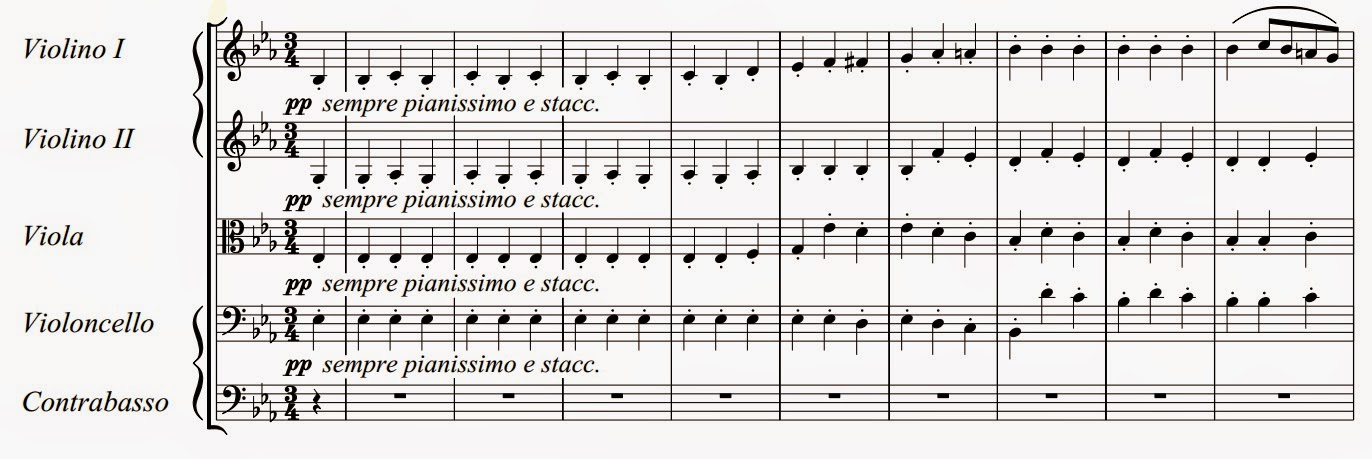

Chopin's 2nd Piano Sonata, Beethoven's is the next most famous. It begins in C minor, always a very dramatic key for Beethoven, with the 1st violins playing the lowest note in their range, followed by the lugubrious first theme that is sparsely accompanied by the other strings. The melodic line of funeral marches are usually rhythmically diverse, and Beethoven's is no exception:

After the oboe expresses its grief with the theme, another theme in the major is played that sheds some rays of light on the dark proceedings, but not for very long. The music meanders into darkness and back to the first theme. A tragic outburst occurs, and the music transitions to a section in C major that gives some little comfort to the sorrow. While this section is in contrast, there is still an underlying tension to the music as two notes are played against three. The section reaches a climax, and after a short transition the music returns to the first theme, but quite soon it transitions to F minor and a fugue is played that thunders through the orchestra. The fugue comes to an end, and a fragment of the first theme is played, after which a section of great resolve and power is played until it too succumbs to the grief of the first theme. The second theme returns for a short while, until the music brightens in a short section before the first theme, fragmented and decaying like the corpse of the hero it honors, is buried after one last howl of grief in the sliding grace notes of the low strings.

III. Scherzo: Allegro vivace - The scherzo of the third symphony must have confused audiences as much as the previous movements, for it runs through the orchestra at the brisk pace of Allegro vivace and is even more rhythmically ambiguous. It is written three in a bar, but in such a brisk tempo the measures fall into groups of two, sort of an optical illusion for the ear:

The accents on off beats that Beethoven sprinkles throughout the movement add to a rhythmic complexity that is not readily apparent in the simple note values he uses. In the trio, Beethoven uses three horns instead of the usual two. The horns play off each other while the rest of the orchestra gives a comment after their phrases. The scherzo returns with changes, with perhaps the strangest change being in the syncopated section that is played a second time in

Alla breve, or two in a bar instead of three. The ear thus staggered, the scherzo continues on its merry, quirky way until the thunderous end is reached.

IV. Finale: Allegro molto - For the last movement, Beethoven defies tradition and writes a set of variations. But these are no ordinary variations, for the bass of the actual theme is heard first and is varied. The true theme is heard in the oboe over the previously heard bass and the music makes more sense. Beethoven had used the theme in two previous works; a ballet The

Creatures Of Prometheus and a work for piano solo Variations and Fugue for Piano in E♭ major that are also known as the

Eroica Variations. The theme is repeated and varied, but the bass itself returns for its own variation, a fugue that uses a portion of it. The main theme returns in variations in high spirits and speed until the music winds down and changes tempo to

Andante. Woodwinds play a lyrical version of the theme, with a section for oboe accompanied by rippling triplet arpeggios on the clarinet. The two against three rhythm is reinforced as lower strings join one clarinet in the triplet accompaniment. The horns nobly play the theme as the rest of the orchestra accompanies. The theme begins to change until the music grows quiet in a short dialogue between woodwinds and strings. With no warning, the music shifts dynamics to a double forte and the tempo increases to presto. Fragments of the theme are bounced around the orchestra. The timpani emphasizes the repeated E-flat major chords as they thunder to finish the movement.

The Third Symphony was premiered in 1805 in Vienna. The reaction was mixed to say the least. As reviewed in the contemporary Viennese magazine

Der Freimüthige:

One party, Beethoven's most special friends, contend that this particular symphony is a masterpiece, that this is exactly the true style for music of the highest type and that if it does not please now it is because the public is not sufficiently cultivated in the arts to comprehend these higher spheres of beauty; but after a couple of thousand years its effect will not be lessened. The other party absolutely denies any artistic merit to this work. They claim it reveals the symptoms of an evidently unbridled attempt at distinction and peculiarity, but that neither beauty, true sublimity nor power have anywhere been achieved either by means of unusual modulations, by violent transitions or by the juxtaposition of the most heterogeneous elements....On that evening, the audience and H. v. Beethoven, who himself conducted, were not mutually pleased with one another. For the audience the Symphony was too difficult, too long and B. himself too rude, for he did not deign to give even a nod to the applauding part of the audience. Beethoven, on the other hand, did not find the applause sufficiently enthusiastic.

The

Eroica Symphony went on to become one of the most played and studied symphonies ever written. It's depth of emotion, craftsmanship and innovation guarantee it an honored place in the history of western music. It is a work that can be heard in different ways for different people, as Arturo Toscanini the famous Italian conductor said when he talked about the first movement of the symphony:

To some it is Napoleon, to some it is a philosophical struggle, to me it is allegro con brio.

Whether listened to from an historical, emotional, or purely musical perspective, Beethoven's Third Symphony is a masterpiece.

When Robert Schumann proclaimed Johannes Brahms as the new Messiah of German music, Brahms was but twenty years old. Schumann was an influential music critic as well as composer, and his high praises were a double-edged sword to the young Brahms. Schumann became mentor and introduced him to other composers and musicians, but Schumann's declaration also put a great deal of pressure on a musical genius who was far from being the master of music he was to become.

When Robert Schumann proclaimed Johannes Brahms as the new Messiah of German music, Brahms was but twenty years old. Schumann was an influential music critic as well as composer, and his high praises were a double-edged sword to the young Brahms. Schumann became mentor and introduced him to other composers and musicians, but Schumann's declaration also put a great deal of pressure on a musical genius who was far from being the master of music he was to become.