The sonata is the first major work he wrote in the key of D minor, and it would be the only piano sonata out of 32 that would be written in that key. It remains one of the most powerful pieces ever written for piano more than 200 years after it was written.

The sonata is in 3 movements:

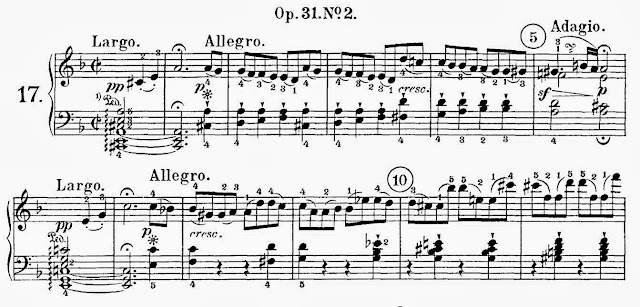

I. Largo -Allegro - Beethoven begins with a slowly arpeggiated, pianissimo A major chord, which is followed by an increase in tempo and 3 bars of eighth note slurs of 2 notes, that rise in volume until the tempo changes to adagio and comes to rest on another A major chord. The first five bars of this sonata form the basis for the entire exposition. What makes this so unique is that this first theme of the sonata contains incredible contrast, something that is usually accomplished in two different themes. Tempo and dynamics change again as another chord is arpeggiated, after which the eighth note slurs reappear, but this time they continue and lead to a theme in the bass that changes to high in the treble as a triplet figure plays in the middle register.

This continues until the two-note slurs of the opening reappear with a different accompaniment. Other related material leads to the first ending before the repeat. After the section is repeated (and in my opinion this sonata needs the exposition repeat) the second ending comes to rest on three G notes. The development begins with arpeggiated chords, this time with more notes. This happens three times, then the music takes off in a double forte repeat of the triplet figure-theme-in bass-and-high-treble material, but in different keys. This continues with heightened drama until a climax is reached when a section of eighth note thirds are played on the first and second beat with a sforzando on the second beat. Then whole note chords and a transition section lead to the recapitulation with arpeggiated chords and two-note slur material, but this time there is a short, unaccompanied recitative inserted between them:

After the A-flat fermata, there is an increase in tension as chords are played pianissimo with rapid arpeggios. This happens three times with an increase in volume until the fourth time the two-note slurs reappear in a different key and accompaniment. More material is brought forth and it leads to a pianissimo ending in D minor.

II. Adagio - This movement also begins with an arpeggiated chord, but the mood is calmer, more reflective. This movement is in sonata form, but without any development section.

III. Allegretto - The music of this movement is constantly moving and full of tension that does not ease up throughout. The quiet ending of the movement gives the impression that the music really doesn't end, but fades into the distance.

Beethoven's compositional style was constantly evolving throughout his career. This brought about experimentation that can be subtle, or as in the case with this sonata, glaringly obvious. His physical malady of hearing loss, which he lamented was getting worse in the letter to his brothers that is called the Heiligenstadt Testament, was written about the same time as this piano sonata. What affect his hearing loss had on his art can only be imagined, as well as what his music would have been if he had not suffered from deafness. Beethoven was one of the greatest musical minds that ever existed, but he was also one of the most human of human beings. It is that quality that makes his music still so moving and influential almost 200 years after his death.

.jpg)