.jpg) The last decade of the 18th century saw the increased development of the traveling virtuoso. Instead of working towards an appointment at a royal court or church, musicians found that they could take their musical facility on the road, get more exposure and perhaps make enough money to remain independent. Mozart was one of the first musicians to go free lance as a composer and pianist, with Beethoven and Schubert following suit in the next generation. But the term free lance needs to be qualified to some extent. While these composers did not have an official position such as Kappelmeister, Cantor or Music director, they still relied indirectly on the patronage of the elite and royalty by way of commissions and other monetary assistance.

The last decade of the 18th century saw the increased development of the traveling virtuoso. Instead of working towards an appointment at a royal court or church, musicians found that they could take their musical facility on the road, get more exposure and perhaps make enough money to remain independent. Mozart was one of the first musicians to go free lance as a composer and pianist, with Beethoven and Schubert following suit in the next generation. But the term free lance needs to be qualified to some extent. While these composers did not have an official position such as Kappelmeister, Cantor or Music director, they still relied indirectly on the patronage of the elite and royalty by way of commissions and other monetary assistance.

Ludwig van Beethoven moved to Vienna in 1792 after he had visited there earlier, and probably got the funds to do so from a patrons who knew him in Vienna and wanted him to move there. He studied with Haydn and quickly became the talk of the town by playing the piano in the salons of royalty and well-to-do citizens of the town. He gained patrons and admirers as well as getting his works published. Three years later in 1795 he gave his first public performance in Vienna.

Beethoven was such a success in Prague during his first visit that he returned in October of 1798, where he played the Piano Concerto No. 1 In C Major in his first concert and the Piano Concerto No. 2 In B-flat Major in the second concert. The Czech pianist and composer Václav Tomášek heard Beethoven in Prague in 1789 and wrote about it in his memoirs:

Beethoven's sketches for the composition go back to 1793, but he performed a version of the concerto in 1795 in Vienna. He kept revising the score, performed it in 1798 , and continued to work on the score until he finished a clean copy for the publisher in 1800. It was published in 1801 and was dedicated to Anna Luisa Princess Barbara Odescalchi Furst, a royal patron and piano student in Prague. The work is in three movements:

I. Allegro con brio - The exposition begins with a march-like theme played by the orchestra. The second theme is in a more laid back mood, but has many key changes which gives an underlying edge to it. With the orchestral part of the exposition over, the soloist enters with a new theme which is only heard this one time. The orchestra reminds the piano of the march-like theme and the piano comments on it. The second theme returns in the orchestra and the soloist takes it up in a recognizable form. The solo piano bristles with scales, chords and running figures. The development section begins in the key of E-flat major in music that is almost like a nocturne. The woodwinds trade fragments of the first theme while the piano accompanies. The key changes to C minor, and then the piano plays descending chromatic scales. The music lowers to pianissimo as the horns play octaves that alternate with chords by the piano. Suddenly the soloist plays a octave glissando in fortissimo that heralds the beginning of the recapitulation. The first theme returns and the piano answers it after a few bars. Beethoven shortens the recapitulation by going directly to the second theme. Secondary material is played until the space for the cadenza is reached. Beethoven himself wrote three cadenzas for this movement, with the last two written ten years after the concerto was finished. Each one of the cadenzas grows longer and more difficult. The recording linked to in this post has the soloist opt for the 3rd version of the cadenza which is extends the length of the first movement considerably. This cadenza is almost a separate work, a fantasia on everything that has gone before as well as some now material. It bristles with brilliance and the difficulties are considerable, not least of which is how to keep such a long cadenza part of the whole of the movement. Near the end of the cadenza there are chains of trills, with the soloist finally playing a wide-spread C major chord, after which the orchestra alone plays a short coda.

II. Largo - The second movement is in A-flat major, a radical departure by Beethoven as it is a key quite distant from the home key of the concerto. The movement is in ternary form, with several themes in the first section that are repeated and developed in the middle section. While the first movement can be called extroverted, this slow movement is more introverted. One of the characteristics of Beethoven's use of the forms of Haydn and Mozart is that he tended to extend the length of movements. The 3rd Symphony In E-flat, has been the most obvious example of this, but it happened earlier than that as with this concerto, written at least 6 years before the 3rd Symphony.

III. Rondo: Allegro - Beethoven keeps the tradition of the Classical era model of concerto final movements with a rondo. The rapid, rhythmic main theme of the movement is first played by the soloist at the very beginning:

After the piano states the theme, the orchestra has its turn. There are three episodes that occur between repeats of the rondo theme. The first episode between repeats of the rondo theme begins in G major. The second episode in A minor, and the third in the home key of C major. But in all three of these episodes, Beethoven doesn't stay in the same key. He throws harmonic and other surprises in each one. After the final episode there is a short cadenza for pianist before the rondo theme returns. The soloist and orchestra then play a coda until the soloist plays another short cadenza as the tempo slows to adagio. The oboes answer this cadenza. There is a silent pause, after which the tempo goes back to allegro scherzando as the orchestra plays the last bars in a whirlwind fortissimo.

In the year 1798... Beethoven, the giant among pianoforte players, came to Prague. He gave a largely attended concert in the Konviktssaal, at which he played his Concerto in C major, Op. 15, and the Adagio and graceful Rondo in A major from Op. 2, and concluded with an improvisation on a theme given him... from Mozart’s “Titus”. Beethoven’s magnificent playing and particularly the daring flights in his improvisation stirred me strangely to the depths of my soul; indeed I found myself so profoundly bowed down that I did not touch my pianoforte for several days....Although published as Piano Concerto No. 1, it was actually the third piano concerto Beethoven had written. The earlier concertos being; a concerto in E-flat written in 1784 when he was 13, and what was published as Piano Concerto No. 2, which was written years before the first. It is all a matter of which one was published first. As the C Major concerto was published first, it is titled as such, and it was Beethoven's decision to have this concerto printed before the B-flat concerto as he thought it the better of the two.

Beethoven's sketches for the composition go back to 1793, but he performed a version of the concerto in 1795 in Vienna. He kept revising the score, performed it in 1798 , and continued to work on the score until he finished a clean copy for the publisher in 1800. It was published in 1801 and was dedicated to Anna Luisa Princess Barbara Odescalchi Furst, a royal patron and piano student in Prague. The work is in three movements:

I. Allegro con brio - The exposition begins with a march-like theme played by the orchestra. The second theme is in a more laid back mood, but has many key changes which gives an underlying edge to it. With the orchestral part of the exposition over, the soloist enters with a new theme which is only heard this one time. The orchestra reminds the piano of the march-like theme and the piano comments on it. The second theme returns in the orchestra and the soloist takes it up in a recognizable form. The solo piano bristles with scales, chords and running figures. The development section begins in the key of E-flat major in music that is almost like a nocturne. The woodwinds trade fragments of the first theme while the piano accompanies. The key changes to C minor, and then the piano plays descending chromatic scales. The music lowers to pianissimo as the horns play octaves that alternate with chords by the piano. Suddenly the soloist plays a octave glissando in fortissimo that heralds the beginning of the recapitulation. The first theme returns and the piano answers it after a few bars. Beethoven shortens the recapitulation by going directly to the second theme. Secondary material is played until the space for the cadenza is reached. Beethoven himself wrote three cadenzas for this movement, with the last two written ten years after the concerto was finished. Each one of the cadenzas grows longer and more difficult. The recording linked to in this post has the soloist opt for the 3rd version of the cadenza which is extends the length of the first movement considerably. This cadenza is almost a separate work, a fantasia on everything that has gone before as well as some now material. It bristles with brilliance and the difficulties are considerable, not least of which is how to keep such a long cadenza part of the whole of the movement. Near the end of the cadenza there are chains of trills, with the soloist finally playing a wide-spread C major chord, after which the orchestra alone plays a short coda.

II. Largo - The second movement is in A-flat major, a radical departure by Beethoven as it is a key quite distant from the home key of the concerto. The movement is in ternary form, with several themes in the first section that are repeated and developed in the middle section. While the first movement can be called extroverted, this slow movement is more introverted. One of the characteristics of Beethoven's use of the forms of Haydn and Mozart is that he tended to extend the length of movements. The 3rd Symphony In E-flat, has been the most obvious example of this, but it happened earlier than that as with this concerto, written at least 6 years before the 3rd Symphony.

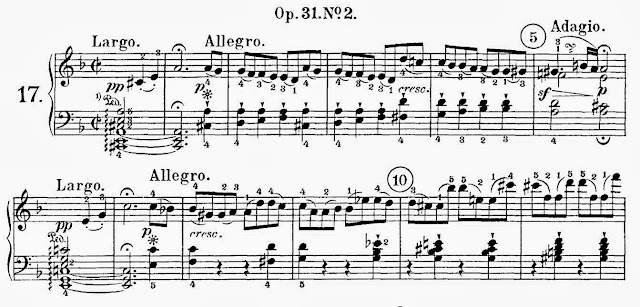

III. Rondo: Allegro - Beethoven keeps the tradition of the Classical era model of concerto final movements with a rondo. The rapid, rhythmic main theme of the movement is first played by the soloist at the very beginning:

After the piano states the theme, the orchestra has its turn. There are three episodes that occur between repeats of the rondo theme. The first episode between repeats of the rondo theme begins in G major. The second episode in A minor, and the third in the home key of C major. But in all three of these episodes, Beethoven doesn't stay in the same key. He throws harmonic and other surprises in each one. After the final episode there is a short cadenza for pianist before the rondo theme returns. The soloist and orchestra then play a coda until the soloist plays another short cadenza as the tempo slows to adagio. The oboes answer this cadenza. There is a silent pause, after which the tempo goes back to allegro scherzando as the orchestra plays the last bars in a whirlwind fortissimo.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)